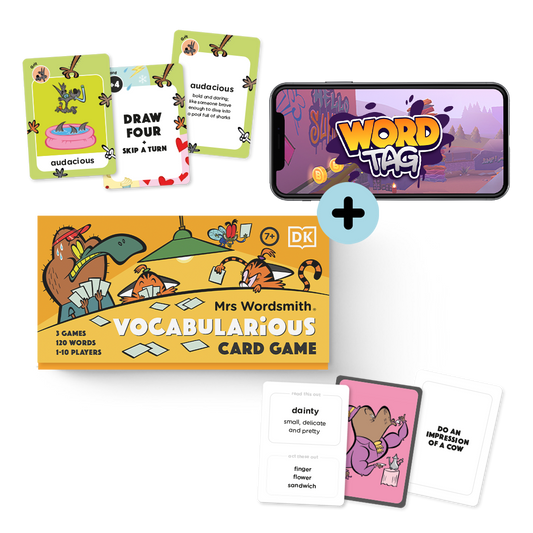

The Mrs Wordsmith team is passionate about the amazing opportunities afforded by games. Founded on the power of storytelling and visual language and with two award-winning card games already, we’re excited about our recent expansion into the virtual space. Set in a vibrant world filled with a delightful cast of characters, exciting challenges, and coins players collect to trade for fun in-game rewards, our new vocabulary app, Word Tag, gamifies vocabulary learning.

Games are not only a great way to supplement a classroom or homeschool curriculum: they have unique features that other educational materials don’t. We started to unpack what makes games such excellent learning tools in our previous post on the ways that video games can turbocharge learning. We’ll continue this series on the benefits of gamification for learning with a deeper dive into the special features of educational games that motivate, personalize, grant agency, and harness the power of social interaction.

Table of Contents:

- Games have uniquely motivating features

- They're powered by engaging visuals

- They're powered by story (and comedy!)

- Game design is tailored and adaptable

- Games give kids agency

- Games promote social interaction

- Download Word Tag and see for yourself!

Games have uniquely motivating features

They’re powered by special rewards

Rewards have powerful chemical effects in the brain, triggering dopamine release mechanisms that keep kids engaged. Educational games can harness these effects by incorporating incentives that books, workbooks, and tv shows can’t. Gamers unlock levels, outfits, abilities, and access other special prizes and motivators like badges, and trophies; many players are so motivated by these types of rewards that they’ll spend hours of effort, and even pay real money, to obtain them. Incentives like this help educational games motivate learners to stay engaged with the material longer (Plass et al., 2015), reinforcing the concepts they’re learning.

Rewards may directly drive game play, like a power-up that temporarily grants a player’s avatar with special abilities. Or, they may be external to the game’s story world, like points that do not affect game play but which determine a player’s position on a competitive leaderboard. Most people get a little thrill when they see their name in the top spot! Rewards like these, together with the feedback players get as they progress, make up the incentive system of a game (e.g. Kinzer et al., 2012), and help motivate players to stay engaged.

Games can also reward performance via increasingly difficult challenges, which boost satisfaction and motivation (Callaghan and Reich, 2018). Unlocking more and more advanced content gives players a sense of accomplishment. According to Kapp (2012), the immediate feedback and gratification that a player receives and the feeling of achievement they get when overcoming a challenge is an important reason why games are such suitable learning devices. Kids can hone skills as they have fun progressing through Word Tag, without noticing they’re learning vocabulary they might normally see in a classroom or textbook.

In Word Tag, for every word activity kids complete, they collect stars and coins which they can use to unlock cool accessories and rides for their avatar, like a scooter that can make them go faster, or a burger that can give them more energy. The gratification kids get from these virtual rewards motivate the learning they’re doing to obtain them! And as kids get answers right, the game serves them words of increasing difficulty. A report on this learning, including what rewards kids earned, is communicated to parents via a weekly progress report.

They’re powered by engaging visuals

Engaging visuals are another incentive powering games. Visually-appealing scenery makes the learning experience more enjoyable. Giving games another extra advantage, research shows that moving images may be even more useful when learning new information than static images. Motion directs attention to important details, which makes integrating verbal and non-verbal information easier. In this way, animated pictures can reduce the amount of effort needed to match up visual input with verbal input (Bus et al., 2014), and facilitate learning activities.

Games can also take advantage of physical device features like touch screens and navigation menus, cameras, effective audio to complement visuals, and feedback mechanisms using microphones and voice recognition (Callaghan and Reich, 2018). This makes for a much more directly interactive and engaging experience than reading a book or watching a video.

If something is beautiful or interesting, humans are motivated to spend more time looking at and interacting with it. Games can create stunning worlds that learners will want to keep coming back to, reinforcing what they’re learning every time they do. The world of Word Tag features engaging settings, like a vivid junkyard, a sunny boardwalk, and a dazzling sandcastle. Kids are free to explore these areas, steering an avatar that they can tailor with cool outfits and gadgets.

They’re powered by story (and comedy!)

Games can tell a visual story, motivating players to come back to watch (and affect) what happens next. Often these stories have comedic beats. Research has found that comedy makes information more memorable (Kaplan & Pascoe, 1977; Banas et al., 2011). Like winning a prize or progressing up the leaderboard, seeing or hearing something funny activates the brain’s dopamine system. Dopamine is a “pleasure chemical” that not only boosts long-term memory but also helps drive motivation (Wise, 2004). Everyone likes feeling good! Jokes matter, and not just to make learning players giggle.

A snake wearing a funny hat, witty characters, and zany villainous street cleaners are just a few of the silly game elements awaiting kids in Word Tag. Gameplay itself also includes comedy. For example, kids are asked to help characters complete funny sentences using words they’ve learned in new contexts.

Game design is tailored and adaptable

Video games are not one-size-fits-all - they can be many sizes, for all. Educational apps should be designed to suit children’s unique learning needs and abilities, because kids learn differently from adults, and from one another. For example, kids have a shorter attention span, so can’t be expected to look at the same thing for too long. Their fine-motor skills are also not yet fully developed. The most effectively-designed learning apps take needs like these into account (Callaghan and Reich, 2018).

Adaptable pacing and differentiated game play based on player input also contribute to making games more tailored, and therefore more beneficial for learning. A meaningful gamified learning experience aligns concrete challenges with a child’s individual skill level, and these challenges increase in difficulty as the player’s skill level improves (Abrams and Walsh, 2014). A digital game can capture performance metrics while kids play. Reports can be created from such metrics that help identify a child’s strengths (like the progress reports in Word Tag, which inform parents about how their child is performing in the game). This feature of games allows communication of a child’s progress to their parent or teacher, to show what words they’ve encountered. Reporting like this promotes real-world reinforcement of concepts, because teachers and parents can work the new vocabulary into real-life conversations to boost learning.

The Word Tag team is implementing a system of personalization for vocabulary learning in the game. The words served in the game will be determined by the child’s performance, so that each child sees vocabulary appropriate to their reading level. The game will track kids’ metrics and data within the game and, based on this, the difficulty of words presented to the child will adjust, to help make sure each child is presented with challenges that are neither too easy nor too hard.

Such adaptability, tailored to each child’s needs and abilities, makes a game feel more personal. This personalization boosts engagement, because if a game is too difficult or too easy, kids might become either discouraged or bored. The potential of games to be adaptive and reflect individual abilities is much more difficult to achieve in other, non-digital learning environments.

Games give kids agency

Kids may not feel like they have much agency (control over what happens) in traditional learning environments. In a game, on the other hand, kids are more in charge. They can control the actions they take to tackle challenges in the game and accomplish goals, and see the immediate impact of these actions. Kids are used to this kind of tailored experience, having grown up with technology that allows for a seemingly endless array of personal choices. In non-digital learning materials, however, there are fewer opportunities for them to take charge.

As Chris Crowell puts it, learning with games “puts the student in the driver’s seat, with the teacher’s role shifting from ‘sage on the stage to guide on the side’.”

Games also offer kids a safe environment to take risks on their own (and fail!) Stakes are high within the world of the game but low outside of it: kids aren’t failing an exam, or failing to answer a question correctly in front of their classmates. Kids expect to “fail” in games - they’re used to it being part of the learning process within a game, trying again and again in order to move on to the next challenge or level (Kapur & Bielaczyc, 2012; Plass, Perlin, et al., 2010). Because of this, kids can feel more comfortable taking risks. They’re free to explore without the burden of feeling like they have to get things right on the first try (Hoffman & Nadelson, 2010). In a game, failing is easier!

In Word Tag, kids take the steering wheel as they explore the virtual world and complete challenges at their own pace.

Games promote social interaction

Vocabulary learning is more effective when it incorporates social interaction and relationship-building. Research shows that kids bond with fictional characters, the educational and psychological benefits of which include increased retention of new information (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015; Gray et al., 2017). In Word Tag, larger-than-life animal characters are the challenge masters, popping up to interact with players and send them in the right direction to tackle vocabulary puzzles and minigames.

A team led by Emily Reardon (2017) found that kids’ emotional investment in characters had implications on their learning experiences. When kids interacted with such characters, their brains registered the experience as more meaningful, leading to deeper learning. Characters also help create an ideal educational atmosphere, because they make children feel relaxed and receptive to learning (Reardon and Kotler, 2017).

Another social element of games is the real-world engagement facilitated by them. As previously mentioned, reports like the one in Word Tag can give parents and teachers insights into the words their kids are encountering in the game. Using this insider info, parents and teachers can reinforce the new vocabulary by working it into family or classroom conversations. Not only does this active interest give kids increased exposure to the words, but it also boosts their self-esteem and motivation (Cheung and Pomerantz, 2011).

Download Word Tag and see for yourself!

Games have special features that other educational materials don’t, and we’ve used these to build a fantastic word-learning adventure in Word Tag. Employing motivating incentives, personalization functionality, and optimising for agency and social interaction, games like Word Tag have psychological and pedagogical power as learning tools.

Ready to try Word Tag yourself, and launch your family into a word-learning adventure? Drawing on the expertise of pros at the cutting edge of education, linguistics, gaming, and entertainment, Word Tag makes learning new words into an exciting quest. Try it for your family today!

https://mrswordsmith.com

https://mrswordsmith.com

Comment

Leave a comment